May was approaching and we needed to head back to start our trip north up the U.S. east coast. I was excited to spend the summer exploring the Chesapeake and sailing into New York harbor.

Sprinting Home

Down at the southern end of the Ragged Islands in the Bahamas, we were about as far away as one could be – both geographically and electronically. No internet or cell for a couple weeks was an amazing way to be fully present in the experience. We went back up to Flamingo Cay and then took the back route, south of Great Exuma, to reappear in the Exumas around Little Farmer’s Cay. Highly recommend that route! It was here we first learned the downside of being unplugged. Brenda’s father had fallen at home and was on the floor for two days before being found. He was now in the hospital and not doing well. We rushed on and quickly made our way to the anchorage at Clifton Bay on the west end of New Providence. It was here Brenda was able to speak with her dad via Facetime. They were always very close and it felt like he had been waiting to say goodbye. Sadly, he passed away the next day. We made it to Ft Lauderdale a few days later and I put Brenda on a plane to Boise.

Lessons in Salty Sailing

I still needed to get the boat north to Chesapeake Bay before hurricane season. Instead of exploring, I found haul-out space at Port Charles Marina. The boat could be left there until we figured out our plans. I reached out to Richard Widmann, a delivery captain, sailing expert, and all around wonderful soul. He had helped me twice in the past. It was a long shot given the last minute timing, but he responded to the situation by squeezing me in. Because of the distance, he also recruited John Dudiak to help us. They arrived just a few days after I had reached out and off we went. This would be a 5 day non-stop up the gulf stream.

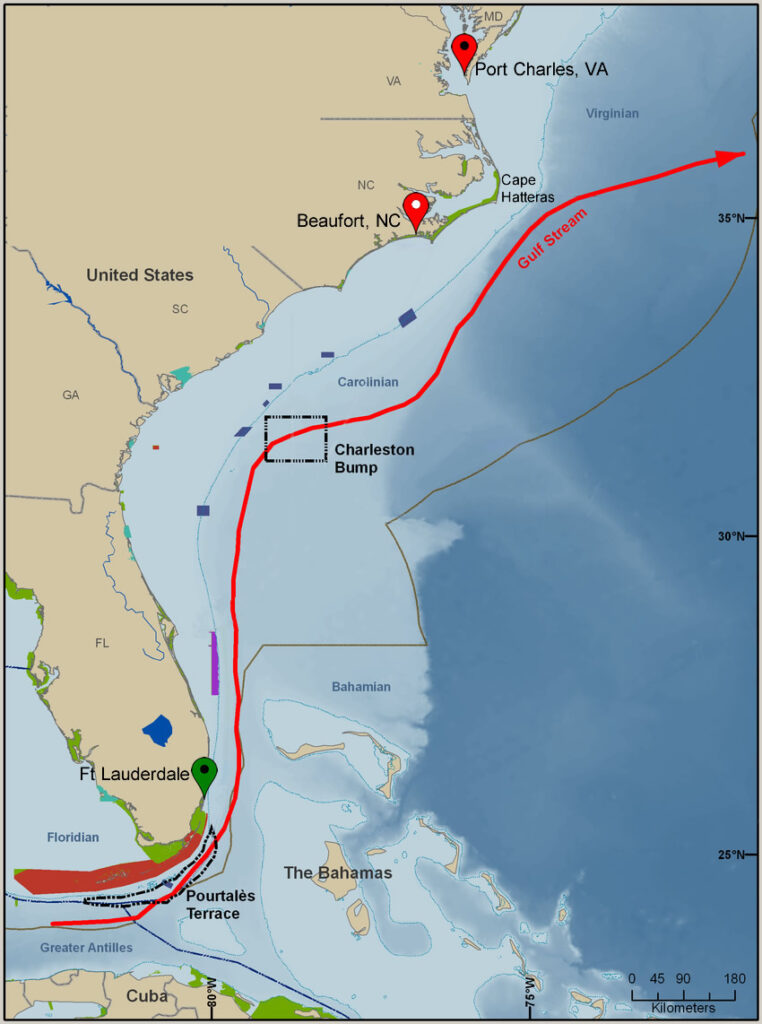

Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream is a strong warm-water current that consistently runs north from the Gulf of Mexico, up the U.S. east coast, and eventually across the North Atlantic. It is miles wide and can run 2-3 knots in the middle. Our goal departing Ft Lauderdale was to head out and ride the gulf stream all the way up to the Outer Banks of North Carolina, giving us a huge speed boost.

The first couple days were beautiful. Sunny and calm, but not great for sailing due to lack of wind. Although we had to motor most of the way, we were making great time.

On the second day we were met by the largest pod of dolphins I had ever seen. A couple dozen played at our bow for over half an hour. Up, down, across – it was quite a show. It turns out filming all this is a lot more fun than playing all those minutes back looking for that perfect shot.

Beaufort, NC

Day three, the fun ended. Richard knew that a front was forecast and that we might be in for strong northerly winds and waves (i.e., coming directly from where we were headed). He had reserved us spots at several marinas just in case we needed to run for shelter.

The seas picked up dramatically and we were smashing into it full throttle on both engines. When you make passage with a delivery captain, this is what you do. It was an expensive lesson.

The crashing waves were impressive! The Leopard 48 is designed with a front cockpit, which means a seating area that forms a very large cavity that could dangerously collect water. It was controversial when first introduced, but there is a large drain (“scupper”) and their claim is that it 100% drains in 45 seconds. I got to witness that this afternoon when a wall of water came over the bow, filling the front cockpit and momentarily putting all of the forward windows under water. Impressively, it all drained out in less than 15 seconds. My assumption is that because this was fast moving water, there was much less actual volume than the static tests performed by the manufacturer.

Around this time, things began to break. First, one of the Antal sliding cars that hold the main sail to the mast broke. The bolt that runs through the middle bent almost 90 degrees. Richard and I went up to the mast, removed the broken slider, and then moved the good sliders around to replace the broken one and leave the very bottom position vacant. I now carry spares of both sizes.

Next, the fishing pole holder on the ceiling of the rear cockpit broke. The large fishing reel forcefully bouncing up and down was too much for it. Another lesson – take down the rod in bad weather. And another lesson – the holder’s design was garbage. They had drilled the counter sink holes so deep that there was only about 1/16 inch left to hold the weight. I fixed it later with a good 1/2 inch of epoxy.

The forecast showed things would only get worse for several days, so we diverted to the docks at Beaufort, NC and enjoyed three days at this great little town.

The Cape

After a few days, the forecast showed the front would pass just after nightfall. Rather than lose another day, we headed out around 3:00pm to ride the cape’s lee while things were still rough and arrive at the critical turn north at Cape Lookout to traverse the Outer Banks during the night after things calmed down. This is another difference between delivering with a bunch of guys and casually cruising with your wife – Brenda would have ensured we wait the extra day. So smart. It didn’t calm down. Not at all. It was worse.

My first high anxiety moment came as we turned north and crossed the Cape Lookout Shoals. Richard has done this many times and has a set of waypoints (GPS points) to guide him through safe passage. We had 8-10 foot waves, crashing rocks all too close on both sides, and I’m watching the depth gauge drop. 20 feet. 15 feet. 10 feet. 9 feet. I have total faith in Richard, but I was really, really worried. Then 10, 15, 20, 30 feet and we were on our way to round the infamous Cape Hatteras.

Cape Hatteras and the Outer Banks are famous as a sailors’ graveyard over the centuries. The area is home to more than 600 shipwrecks. First, two strong ocean currents collide – the cold-water Labrador Current from the north and the warm Gulf Stream from the south converge just offshore from Cape Hatteras. Second, storms are common to the region, including hurricanes and “nor’easters”. Finally, the sandbars of the Hatteras Islands shift significantly due to these rough waves and unpredictable currents.

That night was rough. When I came up at 4:00am for my watch, John told me we took a wave all the way up at the helm. If we didn’t have the enclosure, he and everything else in the helm would have been swamped.

The next day was more of the same, averaging 25 knots directly on the nose, both engines full, and waves crashing. That night, at 5:00am while I was on watch, I heard a loud boom followed by what appeared to be our main sail and lines flapping wildly on the deck in front of me. That’ll wake you up! It was very dark, but turning on the spreader lights I was able to see that our reefing line and our starboard-side lazy jack line, which holds the sail in place around the boom, had both broken. The reef line was oddly secure because it had sprung backwards with such force that it wrapped its frayed end around the stern lifeline and wasn’t coming off until I later forcibly cut it off. The long lazy jack lines, however, were trailing over the side and in the water – right near the spinning propeller. That would be a huge problem. Due to the rough conditions, I didn’t want to leave the safety of the helm, so I put the engine in neutral and began pulling the lines into the helm through the front of the helm enclosure. At this point, I concluded the situation was stable and we were not in danger, so rather than wake people up I waited until sunrise and Richard’s arrival for his 6:00 am shift.

With the sun, we found that the line holding the sail bag up near the mast had ripped out and the batten (a long stiff fiberglass rod) inside the sail bag was coming out. Richard went up with a short line and duct tape to fix it. This was a site I’ll never forget. Waves up to his head, no life vest or tether, climbing the mast steps with duct tape. “How about I give you a life vest and you strap in?”. “It’s ok, it’s all in knowing the rhythm of the boat.”. Well, he got it put back together.

We then had to figure out what to do about the main sail. It was on its first reef, but without a reef line or lazy jack, which means it was partially lowered and the bottom folded section was billowing on deck. Bringing the main sail all the way down without a leeward lazy jack to hold it in would be an unmanageable mess with sail flying all over the deck. I suggested we raise it all the way and maintain our 20-30 degree angle to the wind so that there would be very little actual force on it in these high winds. Fortunately, this worked and between calming and wind shifting we were able to maintain a full sail until anchoring in calm conditions at Port Charles, where Richard and John lowered the sail at 2:00am the next night while I was asleep.

Port Charles

Port Charles is a small town on the relatively uninhabited eastern side of Chesapeake Bay, near its opening to the Atlantic. Because we arrived in the middle of the night, we anchored nearby and waited until morning to pull into the marina. Richard and John rushed off to the airport in Norfolk, while I spent the next couple days preparing the boat for storage. This was my second time laying her up, so I had a list and felt pretty confident. My first time, I had only owned the boat for three days and had no idea what I was doing! With an airplane ticket deadline, layup seems to always involve a string of 14 hour days to get everything done:

- Change oil and filter in both engines

- Fresh water flush dinghy outboard motor

- Secure dinghy in its cover and wrap with lines

- Remove genoa headsail and store inside

- Secure mainsail against heavy winds by wrapping it in rope

- Cover all drains and hull openings (“thru hulls”) with tape to keep out bugs

- Fill scuba tanks

- Empty and defrost all three refrigerators and freezers, and store Snowmaster freezer inside

- Partially fill toilet holding tanks with fresh water and West Marine’s holding tank treatment (ExterminOdor)

- “Pickle” watermaker, which is filling the system with chemicals to prevent sea growth

- Do 10 loads of laundry

- Wash all cushions and bake them in the sun

- Stow electronics in a water tight container with dehumidifier bags inside

- Turn off all circuit breakers and batteries

- Stow all fabrics (clothes, sheets, pillows, etc) in vacuum seal bags

- Wipe walls down with vinegar to deter mold

- Spread DampRid containers all over

Well, you get the idea.

Hauling out here was an adventure. I knew their lift was barely large enough, but this was really pushing it. I’m proud to say that it only took me two tries. There was a 12 knot cross wind and I had a bad angle backing into the slip the first time, so I started all over and nailed it on my second try. There was less than one inch clearance on each side. Yes, those are concrete walls next to my shiny gelcoat.

I had plane tickets for that evening and no hotel, so anything else needed to be completed in the next few hours. Fortunately, it was mostly just a few things that could only be done after it was out of the water, such as covering all the thru-hulls. I had extra time!

It was sad to leave her here in this dirt lot in this remote location, but we’ll be back.